From Fleeting to Decisive: A Dilemma with Value

From the paint brush to the camera lens, an historic and philosophical essay on the transition from impressionist paintings to the modern photograph and it’s meaning in our lives

Part 1: Imperfection Takes the Stage

The impressionist painters, such as Degas, Renoir, and of course, Monet, made infamous the notion that there were precious moments in time that all too quickly faded from view unless captured. Finding such a critical moment of light or expression in the world, these painters moved art from the formal, time-intensive perfectionism of gossamer skin textures and overly wrought scenes into a more fluid, romantic treatment of existence. In this age, things were moving from hand-crafted quality and art as a decadence to mass produced goods and readily accessible services. Suddenly, people began finding value in art that reflected the emergent pace of life. And when we look at Gogh or Monet, we see it: speed, choppy strokes, chunks of color… Look up close, there’s Seurat: a complete mess of nonsensical mush. But move back, take in the whole and you’ll find an entirely new expression of equal magnitude and value for its era.

What these paintings lack in perfection is all but made up for by the admission of imperfection, largely as a mirror to the Impressionist’s time period: the world was quickly moving towards industrialization and with that came the notion of scientific method, reason, and the philosophical tackling of place in the universe. Suddenly society was grappling with a godless world, a non-geocentric point of view, a waywardness that bit down hard on notions of idealism and meaningfulness. Humankind had suddenly transformed from being built by a higher god to a crude byproduct of universal accidents, that, with inaccurate tools had come to discover, for the first time, how lucky and fragile we were to exist.

And what better mirror to express this less than idealistic concept than the Impressionist painting? What the renaissance painters did for fundamentalism, impressionism did for industrial society: it quantized time, stripped away perfection, and humanized our interpretation of reality. It brought with it questions of truth and quality: can reduction to just the essential elements, inexactly portrayed, still be profound?

We know now the answer was a resounding yes.

Ever since, we have been expressing ourselves and identifying ourselves in this inexact ideal. Viewers of such works no longer need to interpret the meaning of paintings by analyzing religious or symbolic juxtapositions, but are free to derive their own meaning from inexact depictions of what remained: the fragile portrayal of this fleeting existence. Ironically, these “fleeting moments” held answers for onlookers in their infinite reluctance to depict any meaning whatsoever. To look at their inexactitude and guess at the effort gave rise to new interpretation and revelation within one’s self.

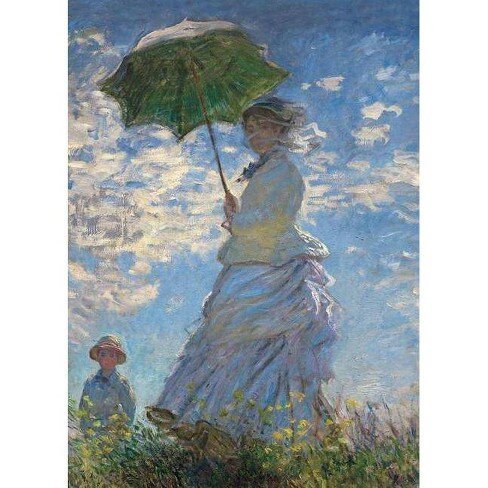

Take, for instance, Monet’s family in the impressionist work “Woman with a Parasol.”

We immediately are struck by the organic colors, the feeling of movement by the wind, the vagueness in his wife and child’s expressions, the lack of placement in time and space else except grass and sky. There’s an omission of detail and substance that releases the viewer from deduction through analysis, and focuses their attention on what’s happening to Monet. Distance, beauty, softness - the gaze of his family towards him.

We feel love in the strokes.

Yet, we also understand a concept via the work that did not occur ever before in painting: Monet has chosen this moment. He didn’t recreate it or labor on inventing it. It happened to him and in a profound choice, he set his canvas up, and expressed his view for our interpretation. (This is at least what we imagine - whether there was some alteration, we can never be sure.)

With that dance of the brush and movement of color, painters gave up their wrestling with higher powers and moved into the realms of mortality and self-expression. Life was suddenly not about any consequential actions leading to the Pearly Gates or eternal damnation; it pivoted in a raucous way to find quality in our passage of time on this earth.

I imagine that this movement, like a lot of foregone conclusions, seems so inevitable and relatable in our lives that we have no trouble denying its pertinent existence. But I do wonder whether patrons and gallery-goers were both aroused and confused, if not maddened, by this transition from the Enlightenment to Romanticism. Here were these young rebels refusing to paint the poignant, traditional scenes of oligarchy and religion that merged art with the greater forces, instead toiling over the mundane moments of existence…

Which brings up the notion of quality in impressionism. We must ask: does the artist’s quick sketch of a fleeting moment contain more or less value than a highly composed Enlightenment painting? This question may more obviously be answered as we look at more contemporary movements such as Cubism or Modernism. Take a look at a Dali or Picasso and the question arises: can Picasso even paint? Where’s the quality if my child could make this? It takes only a quick Google search to reveal that the heroes of modern art had exemplary skills at fine art before moving into such abstracted views. The prodigies demonstrated from very young age a mastery of the basic rules before learning how to break them.

Similarly, we see in Impressionism choices that must have had to be made that showcase a deep understanding for the arts. Issues of light, color balance, layering, detail (or lack thereof)… a preponderance of factors the artist must resolve through aesthetics to portray the given feeling of a moment. Thus we derive value in the understanding and sacrifice that must have been taken to get the artist to a stage where they had the ability to paint a moment, to relate the truth of scene. It is only by the transmittance through a work, the ethereal quality of the artist’s time and toil, that the viewer begins to sense that there is quality and purpose.

In this way, Impressionism unveiled a new form of quality that directly answered societal questions the industrial revolution conjured. More specifically, when scientific discovery led to philosophical refutation of fundamental, theological beliefs, artists used what remained to find everyday moments of beauty and worth that could continue to inspire us all.

Part 2: A Graceful Dance with Realism

Through impressionism, audiences gained an intimate look into an artist’s world, awarding the viewer with non-trivial moments of beauty and value in the face of scientific revelation. So as scientific progress paraded through the end of the 18th and early 19th century, marching towards groundbreaking discoveries of physics and industrial manufacturing, it’s no surprise that the tool-set used to display these impressionistic moments also adapted.

As technological advances came hurtling forward, it also brought previously unattainable goods into the hands of more households. In the early 19th century, new mechanisms emerged to produce mass goods like textiles and agriculture. By transforming manufacturing mechanisms, economies could now support large scale distribution, changing the rules of economics for good. Thus the printing press and horse-drawn transportation not so quietly replaced assembly lines and steam engines, and niche professions could become consumer hobbies.

At the time of impressionism, during the early 19th century, photography was just beginning to emerge as a medium. The application of photography began to evolve as well. At its onset, photography required a technical knowledge that made if difficult for the lay person to either afford or understand. Cameras themselves were took negatives that were very large and scarce, bulbs that shattered upon shooting, or tripods for incredibly long exposures, access to a chemical room to develop negatives, and a knowledge of burning and dodging to produce the correct contrast and exposure… needless to say, photography was either a schooled profession or extravagant hobby for the wealthy requiring erudite knowledge for limited occasions.

Fast-forward to the end of the 19th century, and we begin to see the reduction in size of film and thus camera bodies, so that by the time we have 35mm, photography has become completely portable. Though still widely niche, with advents like the Leica M series and Kodak development processes, people with a passion for capturing their moments could now begin “documenting” everyday life. It is with these series of cameras that the world begins to see events of the 20th century unfold. The news became infiltrated with shots of the war. The photograph, which was once pondered for aesthetic versus scientific properties now comes to embody both: composition, lighting, subject, and fact all merged into one. The addition of fact separated the camera from the brush. No longer were paintings needed to capture royal society or victorious battles afield. As information spread more rapidly with the printing press, the world began to need proof of events. A photo could, without doubt, make something formerly intangible (save by description) a reality.

But it is not until Henri Cartier-Bresson enters the photography scene in the early 1900’s that we see the photograph become something other than just a merging of fact and aesthetics. Bresson, in essence, does for photography what impressionism did for painting. He, with his revolutionary philosophy and expert eye, transformed the photo into a pinnacle of what it could mean to the viewer.

Just as we examined the “Woman with a Parasol” painting by Monet, take the instance of Bresson’s infamous “Behind the Gare St. Lazare” photograph.

The simple composition of this photograph, with much in silhouette, seems not so impressive by first glance. In fact, the photograph may seem quite comical - it is absolutely without the severity of war! And, in reductionist view, the comedy is at the heart of the image: the irony of grace. For on the one hand, we have a man attempting to leap a puddle (we can guess, without much luck). His freeze-frame just above the water stretched in a perfect leaping posture is humorous!

But there is an additional angle to this photograph that sets this moment aside and asks the viewer a question: if all moments in space and time from any angle could be captured, which we be the most poignant? And that revelation is what sets this image apart. Not only has Bresson perfectly timed the man’s leap, using the fact of the image to showcase an instance, but he has also juxtaposed it with a subtly hidden poster of a dancer expressing a much more graceful ballet leap. The viewer can now read much more into the photo, of the contrasts of grace, the fall of beauty, the moment before calamity - hope, tragedy, humor. The photo is immensely accelerated in meaning by the decision to make it at this perfectly timed moment.

Utilizing the (1) rules of painting, (2) fact of the moment, and (3) an uncanny timing, Bresson elevates the photograph from documentary weapon into the world of art. This type of photo, of which he spent his life’s work pursuing, captures what Bresson called the “decisive” moment. It’s a picture from an angle that expresses the subject it captures to a degree that could not better be described at any other moment in time. Compared with impressionism, it’s an even more fleeting moment. (In fact, this type of photo is the one moment that if missed would be of great tragedy for it would be highly unlikely to ever find again.)

Bresson’s work opened new avenues for creative expression. From his work emerged street photography (a combination of elements captured during the quick hustle and bustle of city life). It also gave photographers in general a new level of moment to capture in landscape or home life. It seemed to ask the question: if you could document a subject in just one moment, what would be the perfect expression to define them. We see this in subsequent Bresson works of portraits, such as of Camus, or Picasso, or Capote. All of them embellish the viewer with a sense of who the enigma behind such creative genius might have been, a sort of utmost of their being seen through expression, lighting, and background. Bresson’s photos made intimate and real someone beyond the reach of and idealized by society.

Part 3: A Question of Quality in Modernism

What is the trend we see emerging in the art of capturing something before us? As society progresses and technologies capable of expressing what we see and feel in the world around us adapt, so do the values we formerly held dear. The photograph changed painting in many ways. The documentation and art merger gave painting a push off the modernist cliff to find expression for the viewer more immediate and penetrating than that of what a photograph might produce. Here, we also see a dichotomy bloom: which has more value, imagined or documented reality? Though obviously this is debatable (and is one of the reason’s I hate photography so much), the current situation with photography has more than proved this split a reality. A photo is for documenting the essence of a subject perfectly, whereas a painting is for study of the essences of the things or the emotions that belong to things. Both have purpose, but both are unique in their digestion by the audience.

And here is my struggle: a photograph will always be where the photographer has been, an expression of witnessed instances in space and time. But (typically) it is not what the photographer is or felt or believed in. It cannot abstract the situation into it’s essence, rather it is the world presenting itself bluntly and blindly to a lens. Thus, what are we to say about a photo, except that many decisive moments may be happening as we speak all around the world, and anyone with a camera and either luck or skill may capture it with little to no understanding of what it might mean? The thought is crude and devaluing. Very unlike a painting, where every stroke is intentionally put down to craft a view for all onlookers that resonates with something portrayed…

I can find value in what a person saw, how the photographer used their surroundings to create with composition, light, subject, a view that expresses wholly and deeply the subject, but I cannot and will not say that it has as much value as a painting. A single photograph tends to lack sacrifice, only a body of work carries the true knowledge of time and effort to produce a set of contents that measure up to a painting. That, to me, is what quality represents: a well-defined and carefully crafted expression of a moment or theme. But as the quantity increases as we become a more globalized high functioning society. Especially considering our modern age of omnipresent photographers.

The 21st century has seen an exponential explosion of photographs appearing online by any Joe with a phone. This proliferation of trash has also yielded better and better documentation of decisive moments. We can easily imagine that soon, a well-trained AI could produce the “decisive moment” we want to see by rendering of all these chaotic moments stitched into a fabric of neurosignal and internet connection. Instant pleasure, dopamine rush, a bit of anxiety, or sad silence over a careful re-representation of our world through an AI’s titillating algorithm.

That is to say, as the line begins to blur on what is and what is not real that we see online… as people begin to merge with artificial realities such as VR or AR, we may begin to question how much a photograph or painting is worth. If it could be simulated, rendered pleasing, would it still be as lovely as the fact-produced (once-in-a-lifetime) capture by Bresson or any other? If the AI slightly alters a Bresson to become slightly more exemplifying of the decisive moment, is that not slightly better? How do we judge quality if the AI has removed the sacrifice needed for another human to produce it?

And will society care?

And what comes after a photograph? As technology rates increase, so too will the speed of data transfer. More information pumped into our brains more quickly. Perhaps we’re already witnessing the next evolution in Youtube’s real-time uploads of normal people having incredible moments or situations?

Maybe what comes next is living other’s decisive moments… Yes, as Neuralink embeds itself (literally) into our conscious and subconscious minds, it may also download a Pavorati type moment singing Nessun Dorma for all the world to experience through their own Neuralink. And would that not be more grand?

Whatever it is, we (the onlookers) must decide it’s value. Perhaps as we merge with technology, we will find this value as uniquely personal expressions rather than external observations, each experiencing the world through subjective rather than objective experiences.

Part 4: Conclusions

In closing my philosophical essay on what it means to capture a moment, it is all too easy to see that our art forms have adapted to technology to match the new societal value structures that directly correspond with scientific progress. The lock step nature of technology crafting society and visa versa will all too soon witness greater changes as we become more in tune with technology itself.

Importantly, I leave this post with a provocation: how much of yourself are you willing to put into doubt to render quality of an external representation? Ultimately, we must judge the sacrifice taken to make a work, be it by an algorithm or a being. It is the question of language the art has derived to speak to you. And at the end of the day, that is your language to read into art and its own language to read into you.